Words to the heat of deeds too cold breath gives

Shakespeare, Macbeth

“The Concept” is perhaps the term that I mostly thought of when I wanted to do this recording, my first recording ever. The question that then arose is: what do I want to portray as a concept? How perfect should the sculpture of a face be that really does not belong to me? Or rather, what should “I” present from the scores written by others? And what is my hammer and chisel for making this sculpture?

Music lives in time. Notations are more like tombstones. If the “performance” were an act of resurrection, a recording would be, so to speak, a sculpture of the “moment” and the movement of time, or if music had a life for itself, it would be a picture of a mummy.

With this first pessimistic impression, I started a small search in my mind. A quick search in the recording literature makes clear that at the same time these sculptures have photographed one moment of a life that for years can carry the breathing of the once lived. The live recording of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony by Willem Mengelberg is anything but a mummy, just as any recording by Carlos Kleiber. Even in today’s “Zeitgeist” such lively recordings can be found, specially in the field of the unfortunately so called “Early Music”. So, I see it as my task to stop time, while presenting the concept of time.

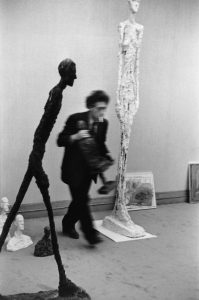

In a conversation with the Iranian photographer Ako Salemi I became aware of the works of the famous photographer Henri Cartier Bresson. Bresson creates a kind of interlaced work of art by, for example, photographing the artist Alberto Giacometti at the right moment next to one of his sculptures, which also has a running posture. The first living subject that I had was the music that was dear to my heart by J.S. Bach and his incredibly creative sons to one of the most humorous composers of all time, L.v. Beethoven, and a very lively and humane suite by A. Schönberg.

In my recording, I tried to run the music of these composers and tried to photograph them, following the example of Bresson. In this experiment, the role of Giacometti is given by the music, but I still feel very far from taking a camera like Bresson in my hand.

The choice of pieces is not linked to an intellectual concept. The fantasies by W.F. and C.P.E. Bach had a prelude-like character to me from the beginning when I started to read them, which convinced to use them as quasi-preludes to the two cycles of variations. The idea was to combine more freely composed pieces with the more stringent variations, but it must also be said that the two variation cycles by C.P.E. Bach and Beethoven both lead to free fantasies toward the end.

The choice of instruments is limited by a simple idea: from among the instruments available to me, Paul McNulty’s copy of a Walter piano was the most appropriate for the texture, sharpness, and articulation of the pieces in the first half of the recording. It was clear to me that, historically speaking, this instrument would not be the most accurate piano for the two sons of Bach, but I am also convinced that this decision will not harm the music.

The choice of the Blüthner grand piano from 1905 was first associated with my love for the Suite op. 25 by Arnold Schönberg. In my opinion, the suite suffers from the reputation of being seen as the first completely dodecaphonic piece by Schoenberg, and the immediate absurd judgement to rate it as a purely mathematical piece that breaks down “romantic” traditions. The absolutely humane and Brahms-inspired method of composition in this suite is immediately obvious. The classical structure of the movements, the intensity of the intervals and the importance of harmony are no less expressive than the late Romantic music literature. The warmth and, at the same time, clarity of the sound of the Blüthner grand piano was a great help to me in trying to get closer to this idea.

In conclusion, it could be said that when a recording is released, it is no longer a part of the artist. If it creates its own life, hopefully, it can share this life with its audience, and even if not, the image of a once-in-a-lifetime movement will remain, like a painting hanging on a wall. The artist is no longer the same as at the time of the recording and will continue observing the flow of time.

Arash Rokni